Breadcrumb

- Home

- The Colthouse Gibbet: Background (Claife))

In 1752, the Murder Act was passed, laying down the punishment for anyone convicted of murder as execution by hanging. However, it did not stop there. The condemned person’s corpse was then either to be sent for anatomisation and dissection - or was to be handed over to the sheriff to be hung in chains on a gibbet, as a highly visible deterrent. The body was usually suspended up to thirty foot high, and there it remained, often for decades, rotting away, treated as carrion by crows and other birds, until finally even the bones dropped to the ground through the chains, to be carried off by dogs or foxes, or even the occasional ghoulish souvenir hunter.

But gibbeting had not been invented by the 1752 Act – it had always been there as a possibility under the Common Law, going back into the Middle Ages; and there tended to be a particular preference for erecting the gibbet at a cross-roads (where there would be plenty of passing traffic), and especially at the boundary between two townships, as a ‘liminal’ space. Actual authentic cases of gibbeting are rare in the records, but one well documented case occurred in 1672, when Thomas Lancaster of High Wray was sentenced to the punishment at Lancaster Assizes. According to the diarist and letter-writer Sir Daniel Fleming, he was accused of multiple murders, killing his wife, her father, her three sisters, her aunt, her ‘cosin-german’ (first cousin), and a servant boy. The poison used was white arsenic – and apparently a number of neighbours were also taken ill as Lancaster tried to pass it off as ‘a violent fevor’ which had affected the neighbourhood of High Wray.

In the Lent Assizes held in Lancaster in March/April 1672, Thomas Lancaster was found guilty – with Fleming adding in a letter to a friend that Thomas had subsequently confessed saying he had done it for a payment of £24 from an heir to his wife’s estate. Whether this was followed up or not is not known. What we do know, from the account inserted into the records of the Parish of Hawkshead, dated 6 April 1672– is that he was sentenced ‘to be carried back to his owne house at Hye Wray where he lived, and there hanged before his owne doore till he was dead for that very fact & then was brought with a horse and a carr on to the Coulthouse meadows and forthwith hunge oopp in Iron Chaynes on a Gibbet which was sett for that very purpose on the south syde of Sawrey Cassy neare unto the Pool Stang and there continued until such tymes as he rotted away bone for bone.

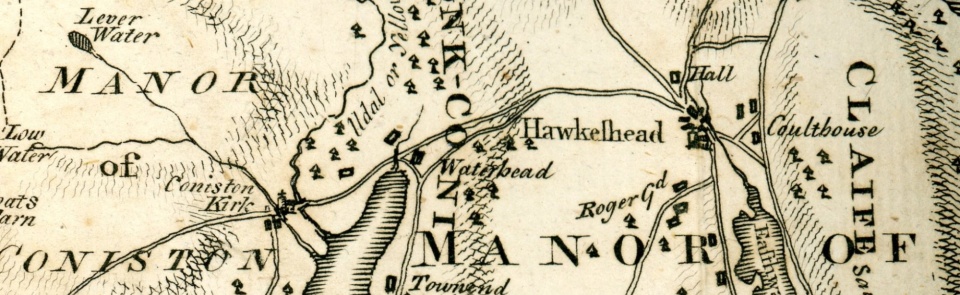

An account published in the Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire in 1865 said the ‘the scene of this exhibition still bears the ill-omened name of ‘The Gibbet Moss’. Where exactly it was is a little difficult to ascertain, as most of the place-names mentioned have been lost. However, Coulthouse meadows may be expected to be the flat – and wet – lands lying between Hawkshead and Colthouse. The road that runs across this from Hawkshead to Far Sawrey, alongside Esthwaite Water, now the B5285, is almost certainly the Sawrey Cassy (Causey or Causeway) – while the Pool Stang is probably the pool now called Priest Pot. The Black Beck, which flows down to Esthwaite Water, formed the boundary between the townships of Hawkshead and Claife. On the 1774 map from West’s ‘Antiquites of Furness’ (actually surveyed in 1748), the spot can probably be identified on the road between Coulthouse and Hawkeshead, near the stream leading to Easthwaite Water.

In or around 1778, a young visitor came to the spot, and recorded his thoughts twenty years later, in his ‘Preludes’. This was William Wordsworth, born 1770, who published the first draft of the poem in 1799. In 1778, aged eight, he had been sent off to Hawkshead Grammar School: and in the poem he recounts how ‘while I was yet an urchin’, he had ridden off on an adventure with an older boy called James. The two became separated – and young William…

Came to a bottom where in former times/A man, the murderer of his wife, was hung

In irons; mouldered was the gibbet mast,/The bones were gone, the iron and the wood,

Only a long green ridge of turf remained/ Whose shape was like a grave…

Several lines later on, Wordworth mentioned seeing ‘The beacon on the lonely eminence’. This has led some people to suggest the whole adventure took place near Penrith, and does not relate to our Gibbet at all. But in fact Coniston Old Man, where in Tudor times there had been a beacon, is visible from near the proposed location of the Colthouse Gibbet.

References:

A Craig Gibson, ‘The Lakeland of Lancaster: No I: Hawkshead Town, Church and School’ Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire, vol 17, (1864-65), pp139-160.

A Craig Gibson, ‘The Lakeland of Lancaster: No II: Hawkshead Parish’ Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire, vol 18, (1865-66), pp153-1774.

Burials at St Michael and All Angels in the Parish of Hawkshead, https://www.lan-opc.org.uk/Hawkshead/stmichael/burialnotes_1568-1705.html

J Richardson, The History and Antiquities of Furness, Barrow (1880). P.77.

Text by Bill Shannon

Image: Colthouse, from West, Antiquities of Furness, 1774, Author’s collection.