Breadcrumb

- Home

- Windermere on ice: the ‘Great Freeze’ of 1895 (Background)

The ‘Great Freeze’ of 1895 followed the ‘Great Storm’ of ’94. That deadly gale swept across Cumbria just before Christmas and left a trail of destruction. Thousands of trees across the county were knocked flat, including the ‘great oak’ that had once graced Graythwaite Low Hall. Then, in the weeks that followed the temperature fell. [1] Then it fell again, and again. One by one the lakes began icing over. Even Windermere froze. Within a few weeks all 10.5 miles of the lake had become a massive makeshift skating rink. In some spots, the ice measured 9-inches thick.

That sort of weather is no good for farming, not in Cumbria at any rate, but it can be ideal for winter sports. Suffice it to say that as the mercury fell, the number of visitors rose. ‘Thousands of people’, as Irvine Hunt has put it, ‘set off for Lakeland with their skates’.[2] Packed trains from Lancaster, Liverpool and Manchester arrived, especially at the weekends. The Lakes Herald estimated that ‘close upon a thousand skaters visited the lake’ on Saturday, 12 January alone.[3] One passenger reported that he left Lime Street Station a little after half eleven ‘this morning, and was on the ice by three o’clock’.[4]

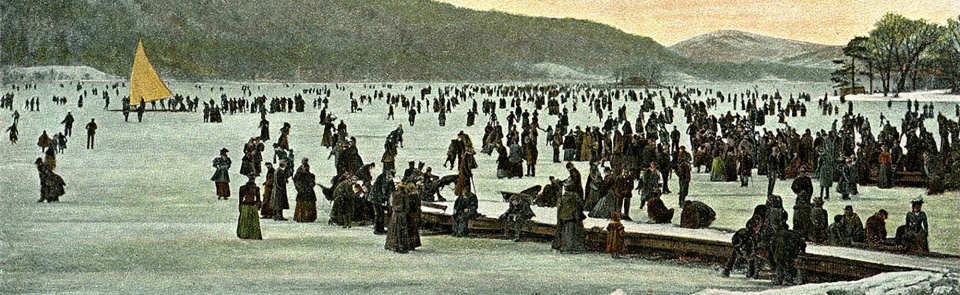

Skating has long been a local winter pastime. Even William Wordsworth was fond of it. One of the most memorable parts of his poem The Prelude describes his childhood escapades on the ice. The Great Freeze of ’95, though, brought out skaters in numbers never seen before. Bowness Bay became an impromptu skating resort. Local bands played waltzes there to crowds of upwards of 2,000 skaters, while other people enjoyed sliding about in sledges, sleighs and horse-drawn carts. There was even an ice yacht that rolled over the lake on glass wheels.

In some cases, moreover, people worked up an appetite playing ice hockey or curling, and then fell upon roasted sausages and hot drinks served at tea stalls – some of which were out on the ice! By all accounts, a carnival atmosphere prevailed, but the local constabulary were on hand. Helmeted, side-whiskered and bedecked in long overcoats, they kept a watchful eye on the proceedings. Some accidents still occurred, however. Notably, a man broke through the ice and drowned. Thankfully, though, few serious injuries occurred.

Similar scenes could be seen on Derwentwater. A painting by Joseph Brown that is now in the collections of Keswick Museum shows a crowd of people from all walks of life wheeling, strolling or tumbling about the lake. On Coniston Water, the reclusive John Ruskin allowed himself to be rolled onto the ice for a family photo. Even for a man who lived as long and seen as much as Ruskin, the chance to glide over the lake was evidently one not to be missed.

As with all good things, the winter carnival eventually came to an end. Spring approached, and the ice began to creek and crack. By May, the Great Freeze had become a memory. But the story of that winter lives on.

The lakes have frozen since then, of course. Some of the splendid photos in the Sankey Photography Archive held at Cumbria Archives show us as much. Visit the Archive’s website to discover more. Still, the lakes have seldom frozen as solid as they did in 1895. Given current trends, it is possible they may seldom freeze again in our lifetimes.

Sources

(1) Henry S. Cowper, Hawkshead: (the Northernmost Parish of Lancashire) (London: Bemrose & Sons, Ltd, 1899), p. 51.

(2) Irvine Hunt, Fenty’s Album (Nelson: Pinewood Publications, 1975),60

(3) ‘Passing notes’, Lakes Herald, 14 January 1895, 4

(4) ‘Skating on Windermere’, Liverpool Mercury, 22 February 1895, 6

Sankey Photography Archive https://www.sankeyphotoarchive.uk/

Text by Chris Donaldson

Photo: public domain